Silencing the Noise

January is a natural time to slow down. My inner animal craves hibernation; it indulges in gentle activities that follow the course of the day’s limited sunlight. My time outside of my work at Uptown Studios is spent mostly in darkness, sitting under a reading lamp with a book, sketching in a journal, enjoying a warm beverage, and going to bed early. The winter is a perfect time to reflect and recalibrate, which also makes it an ideal time for an art residency.

January is a natural time to slow down. My inner animal craves hibernation; it indulges in gentle activities that follow the course of the day’s limited sunlight. My time outside of my work at Uptown Studios is spent mostly in darkness, sitting under a reading lamp with a book, sketching in a journal, enjoying a warm beverage, and going to bed early. The winter is a perfect time to reflect and recalibrate, which also makes it an ideal time for an art residency.

This year, I was awarded a fellowship to attend the Winter Residency at Penland School of Craft in North Carolina. An artist’s residency is a program, often facilitated by an arts organization or academic institution, that supports an artist with space, time, and special resources to totally immerse in their creative practice. Penland’s Winter Residency is a shared-studio program dedicated to working professional artists who are experienced in their mediums. During this independent work time, there are no teachers, no students, and no curriculum.  For many attendees, the residency is focused on creative research, the completion of existing projects, or the initiation of new artworks. The sixty-or-so artists in attendance work across a range of disciplines, with assignments to one of the following sixteen studios: Book, Clay, Painting, Glass, Iron, Letterpress, Metals, Paper, Photography, Printmaking, Textiles, or Wood.

For many attendees, the residency is focused on creative research, the completion of existing projects, or the initiation of new artworks. The sixty-or-so artists in attendance work across a range of disciplines, with assignments to one of the following sixteen studios: Book, Clay, Painting, Glass, Iron, Letterpress, Metals, Paper, Photography, Printmaking, Textiles, or Wood.

As a Californian, the opportunity to travel to Penland School isn’t one to pass up. It’s among a streak of historic East Coast handicraft schools, and there is no West Coast equivalent. The campus is a treasure trove of rare craft tools and equipment tucked away in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The setting is idyllic no matter the time of year. As a professional visual artist, I consider an art residency to be a sacred time.

Play as Research

The Covid-19 pandemic wasn’t a creative time for me. I didn’t bake bread or find joy in virtual calls. I was lonely and disconnected from my usually robust studio practice as well as other working artists. I have always made art of my life, but during quarantine, there was no life to make art of. When isolation restrictions were lifted, I vowed to reconnect with my art practice. While in the greater art world, I am known primarily as a papermaker who operates The Mobile Mill, I had a renewed interest in printmaking. I took an Introduction to Risograph class at Sacramento’s Verge Center for the Arts and got hooked on this fun method of making multiples.

The Covid-19 pandemic wasn’t a creative time for me. I didn’t bake bread or find joy in virtual calls. I was lonely and disconnected from my usually robust studio practice as well as other working artists. I have always made art of my life, but during quarantine, there was no life to make art of. When isolation restrictions were lifted, I vowed to reconnect with my art practice. While in the greater art world, I am known primarily as a papermaker who operates The Mobile Mill, I had a renewed interest in printmaking. I took an Introduction to Risograph class at Sacramento’s Verge Center for the Arts and got hooked on this fun method of making multiples.

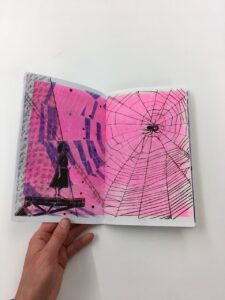

If a Xerox machine and silkscreen methods had a baby, it would be a risograph. This stencil duplicator is seeing a renaissance with artists picking up discarded machines to use in their art practices. The machine is good for making cheap copies – zines and comics, gig posters, wacky monotypes. Ink colors include cheerful fluorescent options; the prints are smudged and perfectly out of control for my work style. It’s thrilling to experiment with layering and collage; discovery lies in every choice and mistake. As the digital design world spins onwards at a rapid pace, I continue to be thrilled by so-called “analogue” art mediums and handicrafts. Methods that require critical thinking and physical engagement are fuel to my creative fire.

If a Xerox machine and silkscreen methods had a baby, it would be a risograph. This stencil duplicator is seeing a renaissance with artists picking up discarded machines to use in their art practices. The machine is good for making cheap copies – zines and comics, gig posters, wacky monotypes. Ink colors include cheerful fluorescent options; the prints are smudged and perfectly out of control for my work style. It’s thrilling to experiment with layering and collage; discovery lies in every choice and mistake. As the digital design world spins onwards at a rapid pace, I continue to be thrilled by so-called “analogue” art mediums and handicrafts. Methods that require critical thinking and physical engagement are fuel to my creative fire.

Seizing Creative Opportunities

While I jokingly refer to residency time as “Art Camp”, it is in all seriousness, very serious business. For myself and the other artists on campus, it is a time for settling in, leaving usual life responsibilities behind, and allowing dreams to be brought to the forefront.

While I jokingly refer to residency time as “Art Camp”, it is in all seriousness, very serious business. For myself and the other artists on campus, it is a time for settling in, leaving usual life responsibilities behind, and allowing dreams to be brought to the forefront.

Opportunities for total creative immersion are hard to come by. I cashed in my prized PTO hours at work and threw all my chips at this invaluable time to tune in. I actively chose to go off the grid. No phone, no texting, no social media scrolling, no work emails. Communication with the outside world is limited to a few hand-written letters sent home to loved ones. Each day I wake with Christmas-morning excitement. Each day is an art-making marathon with no destination in sight. I wake up, drink water, head to the Book Studio, and make art for fourteen hours, breaking only for small meals, short walks, and savored social interactions. Away from my everyday routines and responsibilities, the hours slow down. Every activity feels more intentional and my life’s purpose is suddenly very clear.

Back at home, I dedicate so much of my life time working creatively in service to others – be it through teaching or at my job at Uptown Studios. As such, my residency was a critical “me time” reboot, focused on experimentation and play. I produced a lot of artwork in two weeks – small prints, handmade journals, and some zines. More importantly, I got in touch with my core values. In the studio is where I feel most myself. For me, art is a way of life – it is not a hobby – it is what keeps me alive, curious, and in motion. It’s what makes me care and want to connect with others. It’s what gives me hope.

Back at home, I dedicate so much of my life time working creatively in service to others – be it through teaching or at my job at Uptown Studios. As such, my residency was a critical “me time” reboot, focused on experimentation and play. I produced a lot of artwork in two weeks – small prints, handmade journals, and some zines. More importantly, I got in touch with my core values. In the studio is where I feel most myself. For me, art is a way of life – it is not a hobby – it is what keeps me alive, curious, and in motion. It’s what makes me care and want to connect with others. It’s what gives me hope.

Alongside getting lost in the flow of making, being in the company of other artists who are immersed in their work is invigorating. We are aligned and connected by creative passion, all here together in a state of parallel play. This togetherness makes the Winter Residency extra special. At the end of our time, we come together for a pop-up art show wherein everyone displays and celebrates the artworks that they produced. I leave the Blue Ridge Mountains with a light heart, new friends, and a renewed commitment to my creative practice.

Thank you to the Penland School which sponsored my residency.

Learn more about the artist, Jillian Bruschera, at Two Tiger Press.

Blog